Originally published in French by Clarisse A. Mukundente et Philibert Muzima

On March 10, 2020, the NGO Global Campaign for Rwandans Human Rights published the first of a series of three documentaries entitled “Kizito Mihigo’s journey of the cross: from the explanation of death to death itself”, translated from the original titled in Kinyarwanda: “Inzira y’umusaraba ya Kizito Mihigo: Kuva ku gisobanuro cy’urupfu kugeza k’urupfu“.

New twists and turns of an assassination that has led to unpredictable consequences.

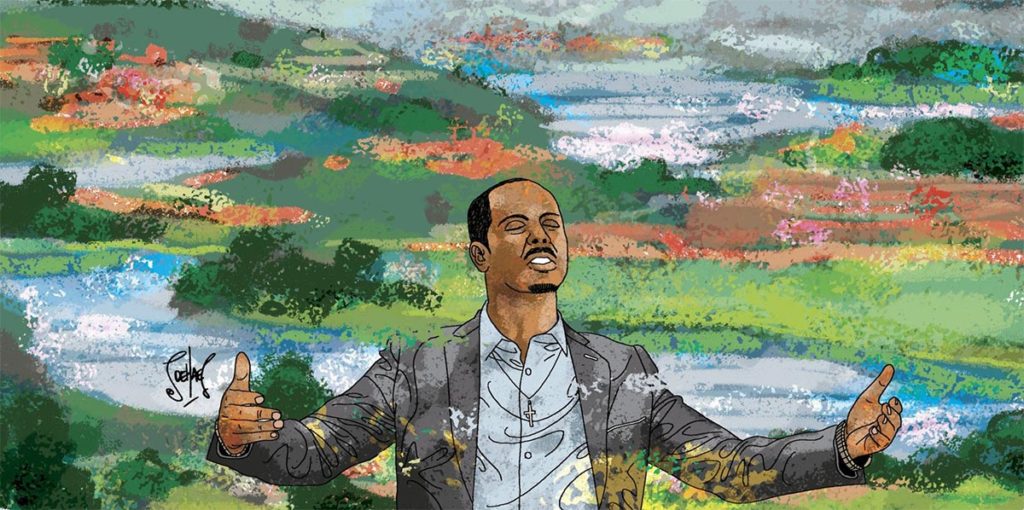

“Until the lion learns to write, every story will glorify the hunter” goes the African adage. If that were so, the brave Kizito would have sold his own skin, defending his life until exhaustion, to deny his hunters the last word.

From within the Kigali hell-on-earth known as “1930” prison, Kizito Mihigo aptly delivered a prerecorded audio message to the world, revealing, undeniable detail. The harassment served upon him from the country’s highest political authorities following the release of his song “Igisobanuro cy’urupfu” (the definition of death). He came close to his own death before being hauled to a “safe house”, where he suffered many more forms of torture: merciless beatings, food deprivation, endless brutal interrogations, harassing visits, etc.

His reprieve from what he believed to be a sure death sentence only came after he conceded to a deal with the devil. And so, with his life in their hands, the torturers extracted from Kizito a confession of guilt. They promised he would die in prison after being sentenced to life, should he refuse the deal! It was after this behind-the-scenes shenanigans that a handcuffed Kizito Mihigo was paraded to the public and interrogated by journalists, nine days after he was kidnapped.

Sentenced to 10 years in prison after a mock trial, he was to languish in the largest prison of death in Rwanda. He managed to establish contact with the outside world, and through a network of friends, he recorded audio messages about the circumstances and conditions of his imprisonment.

In his chronicles, he would also speak about visits by the national police chief, who informed him about obtaining presidential pardon, which Kizito finally obtained after four long years of imprisonment that were both unjust and unjustifiable.

In short, this is a taster of the first episode in a series of three to come. Kizito also succeeded to exfiltrate a manuscript that has been used to draft an autobiographical book yet to be published, posthumously of course.

But the hunters will not budge.

While many are yet to summon the courage to face the painful reality of Kizito’s kidnapping, torture, the masquerade of trial and the ensuing incarceration, and others are trying very hard to refrain from crying, seemingly in another world, the hunters are not budging.

They continue their campaign of tarnishing the image of a righteous man, their irritability aggravated by the bitter realization of the breaches happening right from within the fortress. Their propaganda is articulated in the modus operandi of “Lie, lie, there will always be something left“, which they owe to a certain Joseph Goebbels.

The hunters will not budge, they are unleashed, and they invade the pro-executioner media trying to reverse the narrative. Unlucky for them, they are caught off guard, their comfort alternating ad nauseam with lies and slander bared in plain sight. They believed themselves as the sole storyteller, as the only ones capable of delivering facts.

Their irritability turns to rage inoculated by realizing too late that it is no longer them alone, the predators, who get to narrate the story of the chase. They are enraged by this prey, who has masterfully seized control of his own narrative.

Dying for empathy

Listening to this piece in the series, one is struck by the suffering Kizito endured. All this ordeal just for a song? Even before they searched his cell phone, he had been taken to a forest to be killed.

Let’s analyze the controversial verse of his song: ’Nta rupfu rwiza rubaho yaba genocide cyangwa intambara, uwishwe nabihorera, uwazize impanuka cyangwa se uwazize indwara, abo bavandimwe aho bicaye baradusabira. Genocide yangize imfubyi ariko ntikanyibagize abandi bantu nabo bababaye bazize urundi rugomo rutiswe genocide, Abo bavandimwe nabo ni abantu ndabasabira …… ” (There is no good death whether it be genocide or war, death by revenge, by accident or disease. All those gone, wherever they are now, they pray for us. The genocide made me an orphan, but it should not make me forget others who suffered other forms of aggression not qualified as genocide. These people are also humans and I pray for them).

In this verse, we find all causes of death. They are all judged on the same level as those due to genocide. As a survivor of the genocide against the Tutsi, Kizito was in a better position to understand the pain of other victims who lost their loved ones in any kind of tragedy. François de La Rochefoucauld said that “only those who have suffered are able to understand the suffering of others.”

This is how Kizito, who suffered a great ordeal, was able to translate the message of “Never again” into words and deeds, transforming the hatred he suffered into love as a creed, as a reason for being. This is how he says, in a memorial psalm: “kuko twagiriwe ibyago tuzaba abahamya b’urukundo’’ (because we have known hatred, we are going to be witnesses of love).

Kizito was an empathetic man who could relate to other people’s feelings and this sensitivity was valid for all known and unknown victims. How can one be persecuted because they show empathy? When does such an emotion become an offense punishable by death penalty?

Cynics and sadists unite to explain that in this case, if empathy is not punishable by law, it will be punished by extrajudicial execution.

So, whatever he did, Kizito’s fate was sealed and he was doomed, according to an unprecedented decree of his executioners, to fall from charybdis to scylla.

« …And yet it moves »

Those from outside who do not know Rwanda’s stories might wonder why such a song is controversial.

It is no longer a taboo as by now everyone knows, that in Rwanda there was genocide against the Tutsis. There were also killings against the Hutus. No one can deny that, except those who want to turn a blind eye or deny part of Rwanda’s history.

Anyone who says “killings”, also says “victims”.

This is the crux of Rwanda’s problems. This is indeed the Achilles heel of the current government of Rwanda. The years-running debate about the two-fold truth is ongoing, and even foreign participants have begun to tune in. True deniers bury their heads in the sand and carry on as status quo, because the war against denial is directed towards the so-called genocide deniers, who inherited this abominable label by the mere fact that they dare mention victims of other killings better left unspoken.

Certainly, no one is prevented from commemorating their loved ones. But these Hutu victims too deserve the right to be commemorated publicly, as victims of atrocious killings. However, Rwandan authorities do not like to be told what to do in their domestic affairs, neither by foreigners, nor by anyone else. We live in hope for the day Rwanda will resolve this matter once and for all.

Otherwise, this will continue to plague and potentially hinder national reconciliation as these forgotten victims and survivors start to tell their tales. What’s more, they dislike being lumped with genocidaires, having nothing to blame themselves for. It will be an endless battle.

The survivors of these killings will continue to claim their rights and increasingly gain the empathetic ears and hearts of people like Kizito who will share their pain and support them to amplify their voices and decry the ongoing emotional atrocities.

Will they also be killed? If it is so, then let it be. Instead of retracting, those fighting for the forgotten will say, like Galileo; “and yet it moves!” Or rather, “and yet they are right! … And yet they are entitled!”

Empathy does not rhyme with denial

A friend was grumbling about the disintegration of Rwandan culture. In our culture, he said, there are two events during which even the worst enemies visit each other: when a child is born and when someone dies. The reason is that, at birth, the family grows, and you never know, you could end up in the same family later on through marriage.

Death, because it’s a calamity that strikes everyone and no one will escape it. It seems that Kizito had been reproached for the notable fact of having sung at the masses of families commemorating April 6, 1994. In Rwandan culture, when someone dies, the obituary is delivered as follows: “Family X is sad to announce to friends and acquaintances the death of Y. You are asked to have sympathy and support the rest of the family. “

The plane crash of April 6, 1994 killed, in addition to President Habyalimana, others who were on the same flight. Is it a crime, for a Tutsi genocide survivor, by his own choice, to participate in mass and to present his sympathies to members of the affected families?

Let it be said, “empathy” does not rhyme with “denial”.

In addition, since these are the families of the deceased, is there a difference between the children of ex-President Habyalimana and those of ex-President Sindukubwabo whose daughter is “second Lady” in Rwanda? Why would some families be admirable, and others treated as outcasts?

What is the modus operandi for knowing which person to rub shoulders with, or not, so as not to commit a crime, if there is a crime?

In addition, who determines which groups of people are accessible and which are the untouchables of Rwandan society? Is there an unwritten rule from the ruling authorities, or is it the action of the zealous people who have given themselves the role of Ayatollahs for good relationships between sons and daughters of the country? There are many unanswered questions, even when we know of potentially valuable programs such as “Ndi umunyarwanda” exist.

Headed by the government, Ndi umunyarwanda urges all Rwandans to overcome ethnic hatred and even embrace their offender.

We must know what type of reconciliation is in place in Rwanda. Explanations are necessary to avoid a crime that can lead straight to death!

What is this society that kills a man like Kizito while rolling out the red carpet to a genocidaire like Lewis Murahoneza?

What is this society where an army chief of staff hugs an ex-FAR general and commander of the FDLR under applause, aiming to underline this sign of reconciliation, while one cries of treason when a genocide survivor does the same for a survivor of the camps in ex-Zaire?

Above are two good questions for the whole of Rwandan society, but, above all, they are addressed to genocide experts and specialists who, in general, multiply conferences and symposia to explain post-genocide Rwanda and “Never again».

Originally published in French by Clarisse A. Mukundente et Philibert Muzima