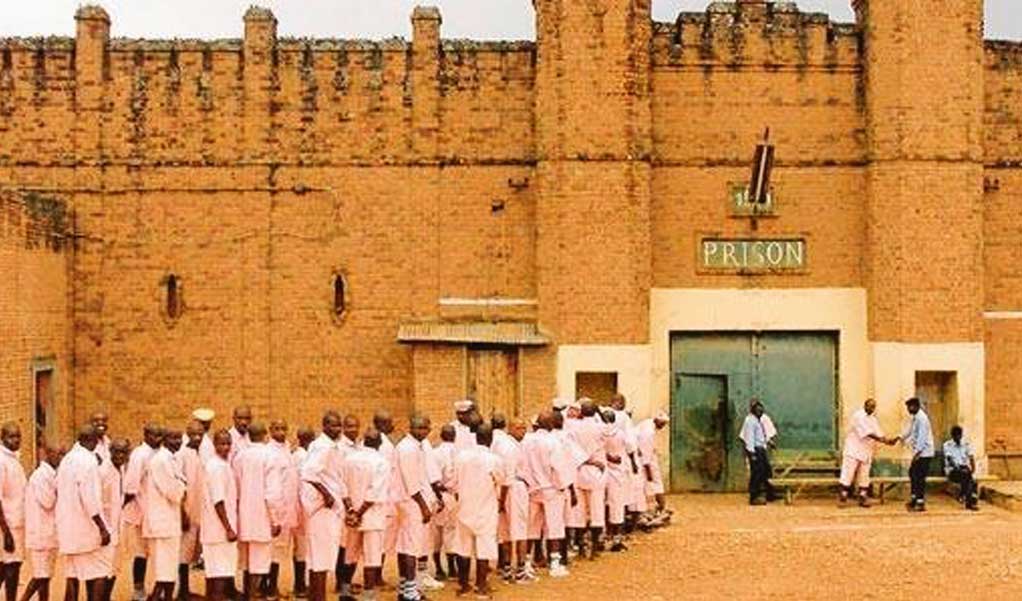

Imagine that you are 18 years old, with your life ahead of you and your head full of dreams. Like the majority of Rwandans, you are in the aftermath of the genocide perpetrated against the Tutsis in 1994. You were almost killed during the genocide and now you are trying to rebuild your life. You have begun the process of resuming your studies in mathematics and physics, subjects you excelled in. But instead, overnight, you find yourself in the central prison of Kigali, known as the 1930 prison. In your new world, “prisoners are neglected, the sick are sent to hospitals to die because they are transferred too late. The fate of Rwandan prisoners is never mentioned; their suffering, the physical and moral torture they undergo”. How would you have reacted? Only a few people can testify about such circumstances, including Kalima, who experienced this misfortune. He shares his story, his downfall, his recovery and his current challenges.

Who is he?

Kalima was 17 years old at the time of the genocide against Tutsis in Rwanda in 1994. He lived in the city of Kigali, and he was a student in secondary school. He lived with his younger siblings his mother. Their father had passed away before 1994. During the genocide, he was almost killed in two or three cases and each time, neighbours who knew him saved him. He had a Hutu identity card but his look was affiliated with the Tutsi ethnic group. When the war approached their neighbourhood, he moved with his family to another place and they stayed there until the RPF-Inkotanyi seized the city of Kigali. He then fled the war to Goma and stayed there for only two weeks until he was separated from his family and returned to Kigali.

How did he go to prison?

It started when his friend told him that someone wanted him dead, but he didn’t pay it any attention. That day, in the evening, he was approached by three soldiers on the street who asked him if he knew of a certain person. The person in question was himself. He had an instinct to answer that he knew the person, without informing them that it was himself, and directed the way to his parents’ home to the soldiers. From that moment he moved to another neighbourhood, away from where his family lived. He informed his mother of his new whereabouts and from time to time he would briefly pass by the family home.

On January 24, 1995, he was walking down the street when a soldier called out his name and greeted him. The soldier told him that the brigade commander was looking for him, and Kalima could never have suspected that it was to put him in jail. He followed the soldier and when he arrived in the brigade, the soldier said “Here comes an Interahamwe!“. Kalima didn’t have time to understand what was happening to him. He describes: “The soldiers assaulted me and beat me up, they brought me where they registered new prisoners, it was the beginning of the Way of the Cross.. He remained in the cell until February 1, 1995.”It was a beautiful day in February 1995, when around 3pm, we heard a soldier, Rukara, calling13 names from our cells, including mine. He asked us to take our belongings and the other inmates began to congratulate me, thinking I was going to be released. If only they knew“, says Kalima. Outside, a pickup truck was waiting for them. They went inside, three armed soldiers accompanied them, and “the journey to hell began“. Fifteen minutes later they arrived at the central prison of Kigali; the 1930 prison. They arrived there around 5pm.Once there, the soldiers who were guarding the prison beat them up before bringing them into the prison. Kalima:”I entered with fear in my stomach, not only was I afraid to find many Interahamwe, those who killed people, but I also wondered how I would survive this prison as a young 18-years and 5 months old boy, who was timid and introverted?”. Once inside, a person exclaimed; “They’re starting to lock up Tutsis too?”. According to the penal procedure of the time, they should have been questioned by the public prosecutor; the only authority that was empowered to place people in pre-trial detention, but Kalima says; “This step was skipped, who cared about the procedures anyway?”.

The first steps into the prison

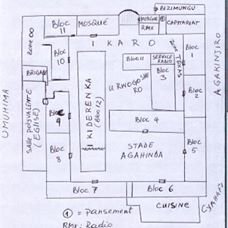

The registration in the prison was done in two steps. First they were registered with the Capita General[1], they were given a blanket, a plate and cup and then assigned to their cell blocks. The prison was divided into 12 administrative blocks and prison staff tried to balance the number of prisoners per block. At the time of registration, a former neighbour recognized Kalima and followed him through the second step. This step consisted of registration in the assignment block. Kalima was given the number 521. There were already 6,000 prisoners in a prison with a capacity of 2,500 people. This figure reached 10,000 prisoners during Kalima’s stay in prison. Kalima would wait in line for 3 hours before he could get food . His meal consisted of corn paste and beans, half of which were stones. “It didn’t surprise me, because at boarding school you could find stones in your beans”, he said. He went to eat at his neighbour’s place, his neighbour made sure that Kalima got a place to sleep by taking him to a section called “mu kiderenka – in delinquency” and by buying prison space for him at 200 Frw, he also gave him an extra blanket. The prisoners were sleeping on the floor and used bricks as pillows. Kalima’s makeshift space was 40 cm wide and 2 m long. A few meters down, some people were discussing how they had killed people in the Genocide and it gave him chills. “I didn’t sleep that night. I hadn’t realized just what my new world was yet and I would learn later that it would be common to hear such stories. The prison would become my new home for the next 3,830 days”, he says.

Prison as a university

A few days before his arrest, Kalima had registered in a school to resume his studies of mathematics and physics. During the first days of prison, he was carefully listening to the announcements, naively thinking that they (those who had arrested him) would realize that they had made a mistake and let him go. In prison jargon, he was still a “umuselire – newcomer“, and little by little he realized that he had entered another university, the one of a hard life, and that mathematics and physics would be for later. It was only after two weeks that he had his first visitor. His family had not heard from him since his arrest and it was the neighbour’s wife who informed his mother that her son was in prison. Kalima: “On that first visit, I didn’t talk to my mother, she couldn’t stop crying.”

Kalima was getting used to the hard life in prison. The corn paste had become tasty, and spending three hours in line to go to the toilet or to drink water seemed normal to him. He had just gone from the newcomer’s rank to that of the “umupeuple – a person used to prison.” He was no longer shy, nor a student; he had become a prisoner. “The first few days are so difficult, but the more you get used to life in prison, the sooner you accept fate, the easier life in prison will be. The only choice we have is to be mentally strong, otherwise we crack under the difficult life in prison.”. It took Kalima two months to start getting involved in prison activities.

The organization of the prison

Inside the prison, there was an organizational chart with the different departments and their responsibilities. The head of the prison was called “general capita” and his office composed of the secretary general and a steward. Food, soap, and other utensils were distributed in the 12 administrative blocks. The prisoners were registered according to the blocks that catered to them; each block was managed by a “capita“, assisted by a secretary. There was a security service headed by a Chief Brigadier, assisted by two Sub-Brigadiers and a secretary. Each block had its own security staff, whose manager was called an advisor, assisted by a subadvisor. There was a hygiene service, a medical team and a radio station “Radio Mouvement Xaveri (RMX)” which kept prisoners informed. Finally, there was a Socio-Educational Support Service (SESE) which provided training for prisoners with a varied range of lessons.

The judicial aspect in prison

- Arbitrary arrests

In Rwanda, after the RPF-Inkotanyi came to power in 1994, the new authorities began to arrest people and put them in prison, accusing them of having participated in the genocide. Many would be lured away from their homes by soldiers or RPF cadres (abakada), who told them to follow them to clarify a small matter (gusobanura akantu gato). These people never returned home again.”25 years later, they are still clarifying“, Kalima said. Other people were arrested following senseless accusations from their neighbours. The people accused had not necessarily participated in the genocide, but they were targeted because of jealousy, the settling of scores between neighbours, pure hatred or extremism.

Another reason why people were arrested was because of their physical characteristics. RPF soldiers would claim that these people had undoubtedly killed Tutsis, even if they did not know them at all and there were no accusations against them. Most of the people arrested were tortured to the point of accepting responsibility for crimes they did not commit, without realizing the consequences. People were beaten to the point they forgot their own names. Sometimes the soldiers invited those who had accused the person to participate in the beating. Kalima recalls a case: “Gasogi, had his hands tied at the back, in a style used by the RPF (ingoyi), and the woman who had accused him was called and she peed in his mouth“.

- Arbitrary detentions

Only a part of the people who were arrested made it to prison.. They would sigh with relief that they had escaped death when they arrived at the prison. Indeed, after being arrested, Kalima told us that “people were being held in holes in the ground, for example in Mount Kigali, and soldiers were slowly killing some of them and throwing their bodies back with those who were alive, in order to frighten them. They could not feed or wash themselves, and their bodies and clothes were covered with lice. The luckiest were found by the ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross), which registered them and they could no longer be killed by RPF soldiers. Detention was arbitrary, unjust and illegal“. The fate of those who were imprisoned has notbeen properly documented or is largely ignored. According to Kalima, “it was part of a sinister plan to bring part of the population to their knees.” By July 1994, the first group of people had already been arrested and detained in Rilima, including the late Ambassador Sylvestre Kamali and others.. When the Kigali Central Prison was reopened in August 1994, its first prisoner was Hassan Nkunzurwanda (Ndanda), a footballer.

- The case of Kalima

From 1995 to 2001, Kalima did not meet any prosecutor. He was languishing in prison without knowing what he was accused of. In 2001, the management requested a list of prisoners who had never been at the prosecutor’s office, and once the list was made, the deputy prosecutors began to question them one by one. On his turn, he met the prosecutor’s substitute, named Ndibwami Rugambwa, who asked him to state the names of the people whom he knew and who were killed during the genocide. In good faith, Kalima provided him with the list and the substitute promised that he would investigate and come back to him. Three weeks later, Ndibwami came and charged Kalima with killing the people Kalima had named. When he asked him if he had any evidence, he told Kalima that he was the one who had to prove his innocence. Kalima: “From that moment on, after 6 years of illegal detention, I was formally charged with a case that was handled and dismissed in a non-professional manner. The universal presumption of innocence was violated“.

- The Gacaca in the prison

With more than 150,000 prisoners, the Rwandan government decided to set up the Gacaca courts system to speed up genocide trials. This system resulted in an information gathering process (Ikusanyamakuru) in the 1930 prison. Prisoners were asked to list the people who were killed between October 1, 1990 and December 31, 1994, who killed them, where and which weapon they used. The inmates gathered in their cells according to where they lived in 1994. The exercise did not produce the expected results. The majority of those listed were Hutus killed by the RPF. All the information collected was requested by the prison management to never be seen again and the prisoners were then asked to only list Tutsis.

- The conclusion

According to Kalima, anything was done to break the prisoners emotionally. Some cracked easily and others resisted. Most of the prisoners were not formally charged, though they were treated as convicts. At the time, the principles of justice were backwards in Rwanda, and one would be considered “guilty until a court has proven otherwise“. For about 7 or 8 years, the soldiers would come and randomly select a few people from the “group without charges” and those selected were never seen again. Kalima thinks they were being killed. The prison was overcrowded, the prisoners had difficulty breathing and were left at the mercy of diseases such as cholera, dysentery and typhoid, which killed thousands of people. There was no hope and “the prisoners called on God to die in peace“.

Daily life in prison

- The visits

Prison functions as a country within a country. Prisoners were entitled to a family visit once a week. Students and workers could visit on Friday or Saturday, after presenting evidence of their status, such as a school card. Young children were allowed one Thursday a month, then they added on a Wednesday. The visit was not individualized; it was in a huge crowd and lasted 3 minutes. Exception was made for people who had medical evidence proving that they could not eat food from the prison, they were entitled to a daily visitor to bring them food.

The society in prison resembled any other, prisoners were not equal. Those who had a family that took care of them were in advantage. The ones who did not have any visitors had a difficult life as the food rations were low.

- The food

Prisoners were deliberately starved. Kalima describes the time when the jailers developed a sinister plan to slowly eliminate the prisoners : “They roasted and mixed glass in sorghum (a cereal used to prepare the prisoners’ porridge). Imagine if you were given glass to eat“! There were also the times when “the prisoners went 3 days without eating, the weakest would die and the day they decided to bring back the food, others would also die because they would eat too much, without knowing that after such a long time of fasting one has to eat a small amount“. The worst time concerning food was in May 1997 when Kalima recalls “we only ate 8 times during the whole month, sometimes there was food and no firewood or vice versa, people went to bed at night and did not wake up…”

The food was of very poor quality. “There was this bitter corn flour and rotten beans (imungu)” Kalima said. As for the quantity, it was a cup of beans and a few grams of corn paste per person, and rarely cassava paste would be distributed, but it was so thin that the prisoners had nicknamed it “the crumbs“. Generally, the menu was a mixture of beans and corn (impungure) served by a quantity of two cups per person.

For extra rations, you had to be part of the supervision or kitchen team; in that case you were entitled to a double or triple serving. In addition, when a person worked for others, such as washing their clothes, queuing in their place to look for food and so on, the person was paid in food.

In 1995, when ICRC began to provide supplementary biscuits and multivitamin tablets, the situation of the prisoners improved a little. Some prisoners refused to take the tablets for fear of becoming sterilized.

- Resourcefulness

Technically, prisoners were not allowed to own money but they did. There were many small businesses; for example hairdressers, selling goods, those who ironed clothes, tailors, and those who fetched water for others. One could work in prison, as a capita or security guard, or work in the kitchen, if he agreed to be paid in food or in other benefits such as not having to queue for services (such as food distribution, collecting water to wash, meeting visitors). There was also the possibility of being part of the production team that could go out of the prison, for example to do construction work. The SESE (Socio-Educational Support Service) provided various training courses. Many of the prisoners learned trades there and used them for their livelihood when they were released from prison. For Kalima, the greatest benefit for the inmates has been for the illiterate who learned how to read and write in prison.

Furthermore, there were rooms everywhere in the prison reserved for prayer. There was a house for all Christian denominations, and they alternated to pray, and Muslims had their mosque.

- Medical care

In each block, 5 prisoners were registered per day and every morning a lot was drawn to choose those who would be taken to the infirmary outside the prison. Non-prison nurses were managing the infirmary and they were assisted by prison doctors and nurses. Inside the prison, there was a hospital run by prisoners and when one fell seriously ill at night, one was carried by the Red Cross to this hospital to receive first aid and the next day he was taken outside. The most complicated cases were sent to the Kigali Hospital (CHK). It was the head of the infirmary who decided on the cases to be transferred to the CHK and the prison director gave his consent. At the CHK, it was prisoners who took care of the hospitalized inmates as it was not allowed for their families to do so. The medical service, composed of incarcerated doctors and nurses, played an essential role by raising awareness among prisoners in the fight against contagious diseases and awareness on health and hygiene.

Sometimes prisoners would raise funds through “the collection for the sick”, to help prisoners who could not afford to buy their medicines, but this was not enough to acquire all the medication needed.

- Living it together

In general the prisoners lived well together, but like everywhere else, there were small problems. Prisoners fought for power to the point of conspiring against each other. For example, they would accuse one another of preventing others to confess to the charges brought against them, so that they could be transferred to another prison. It could also happen that a person who has put others in prison, was also imprisoned in turn. In such a case, the first few days would be difficult for this person, but after a few days, even the people he imprisoned could just talk to him. There have been very few cases where prisoners have fought. In general, there was a good atmosphere in the 1930 prison and the security officers did their job well by putting anyone who wanted to bring trouble in a dungeon (inside the prison). People talked about ethnic groups sometimes, but they didn’t care about them. The main concern of the prisoners was to “get out of prison“. In 2005, before Kalima left the prison, there was a malicious climate linked to the Gacaca courts inside the prison, and some of the prisoners were going to ask for specific security measures because they did not feel safe.

- Children in prison

Kalima says that there were many young people in prison, much younger than him. They were active in youth movements such as the Xaveri, Scouts, YCW or Red Cross.

There was a general Capita, who had been a teacher in secondary schools and he ensured that the young people were involved in security, hygiene or cooking services, and a small part of them, including Kalima, was involved in administration tasks. Although homosexuality and prostitution were prohibited in the prison, sadly, some youth under 18 years of age were forced to prostitute themselves in order to survive, for example in exchange for a supplementary food serving. A small proportion of the young people fell into drugs.

“Putting children in prison is damaging them, they are released with many wounds, some of them have become dangerous criminals. If they were imprisoned while they were innocent, they come out with a lot of anger and discontent“, Kalima said.

- The consequences for families

Basic necessities such as food were rare commodities in prison, so prisoners depended on their families, who were already exhausted because they had been deprived of their main breadwinner. This is the first consequence for families.

Moreover, family members would put pressure on the prisoners to confess, because they were told that people stay in prison because they did not confess. The family members on the outside could start doubting their imprisoned relatives, and there were scenes where “children who came to visit their parents told them that it was their fault if they were still in prison, that if they had confessed they would have gone out“. And some families stopped coming to see their families for this reason.

The prison guards or soldiers took advantage of their situation to abuse women: “I was there when women who came to visit their fathers, brothers or husbands were brought to sleep with the soldiers or guards, including Sub-Lieutenants Beni and Kayijamahe, Sergeants Emmanuel, Valens and Sibomana, before they were allowed to see their imprisoned relatives“.

- The specific case of his family

In July 1995, Kalima’s mother did not visit for two weeks. He was starting to worry when he learned that she had also been arrested. “One Friday afternoon, one of my fellow prisoners who knew her, informed me that my mother was now in prison (women’s ward) and that she had asked him to tell me about it. I was so devastated and hoped that she would be released because this woman could not even hurt a fly“. Kalima saw her on Sunday at church in the Roman Catholic Mass. Seeing his mother in a pink uniform and her head shaved, as is common in Rwanda, broke Kalima. His mother smiled and greeted him from afar because contact was not allowed between the prisoners.

The following Friday, on the occasion of the special weekly visit allowed between male and female relatives, Kalima saw his mother: “She continued to struggle to get used to the reality of prison life and hoped to get out fairly quickly and that things would return to normal”. Between the allowed visits, Kalima and his mother sent paper planes to each other to communicate. This was how male and female prisoners communicated with each other, though it was forbidden but prisoners bypassed it.

In October 1997, Kalima’s mother became ill and was transferred to the Kigali hospital (CHK). Red Cross members informed Kalima and he was allowed to visit her 3 days before her death. He spent 7 hours at her bedside: “I could see that she was fragile and could not manage it“. She kept a brave face and told her son that they would be released, that God could not allow such injustice to continue. His mother’s wish was that her son would be released before her so that he could resume his studies. Kalima remembers the passage from the Bible that his mother had glued on her hospital bed: “Two things I ask of you, Lord; do not refuse me before I die: Keep falsehood and lies far from me; give me neither poverty nor riches, but give me only my daily bread. Otherwise, I may have too much and disown you and say, ‘Who is the Lord?’ Or I may become poor and steal, and so dishonor the name of my God“. Proverbs 30:7-9. That day Kalima and his mother talked about many things.

On November 04, 1997, Kalima woke up with a back pain, something unusual for his young age, and a bad mood. Later in the morning he was called to go to the prison social services where he met his cousin who brought him the worst news of his life: “My mother had breathed for the last time, I burst into tears“. He went back inside the prison, he didn’t want to talk to anyone. The bad news spread quickly in the prison and many prisoners came to see him to comfort him: “The more people tried to comfort me, the more the news hurt me, the sadder I was. My best friend had left, the woman who endured the injustice of a regime that was obstinately determined to make part of the population suffer was now gone. She had taken with her hopes of seeing justice, her dreams of seeing her children grow, her dream of becoming a grandmother. She had also left with the pain and suffering of having seen her children’s lives shattered, of leaving them young to face a world full of hatred by themselves.” Kalima was not allowed to go to bury his mother, because of “prison life” but was comforted that she had a dignified burial.

The second birth

Kalima was released from prison on July 29, 2005, when all persons under 18 years old during the genocide were released from prison. He was unable to return to school because he lacked support. On the day of his release, Kalima had mixed feelings. He was happy to finally regain freedom, but at the same time feared reintegration into society: “I was afraid that people would attack me and I didn’t know where I was going to live, I was a teenager when I went to prison and I had become a man on release, I didn’t see myself living at someone’s place“.

The prison had destroyed his family. They were fatherless, Kalima, the eldest of his family, being in prison had meant one less support for his mother and younger siblings. His mother’s imprisonment was harmful for the rest of the siblings who grew up hurt, to the point they refused to visit their mother and older brother in prison. It was thethe extended family that had taken care of them. When Kalima was released from prison, he went through a re-education camp for a month. He says: “We were taught the gospel of the RPF“, after which they were given the papers to go home. They had to go to the prosecutor’s office every last Friday of the month. Once outside, the first advice Kalima was given was to “live by walking on eggshells because people had changed a lot“. Kalima’s appreciation of Rwanda after prison was that “the country had changed a lot, people, culture and behaviour had changed. Rwanda frightened me, I didn’t see myself in this Rwanda”.

Life after prison was difficult, Kalima could not get used to it, he felt the stigma of having been imprisoned for the crime of genocide even though he was innocent. Whenever possible, he tried to hide it and so he didn’t stay in Rwanda. Eventually he went into exile. Despite the harshness of life in prison, it was a school of life for Kalima where he learned English, customs clearance, project studies and construction (theory). In retrospect, he says: “prison broke my dreams and left me with a deep depression from which I still suffer“.

Kalima’s request to the world is to not believe that all people in rwandan prisons are criminals: “There are innocent people who are in prisons because of false accusations or because the strongest put them in prison, or they are in jail because they were envied or hated“.

He encourages people who have their loved ones in prison to go to see them, to not abandon them, because life in prison is very hard. “If you can’t go, send someone else in your place“, he says.

Finally, he emphasizes that there are also positive things in prison such as “people living together, it is a school of life, if one stays there for a short time one would come out with new perspectives on life, but when one stays there for a long time, the prison hurts“.

Life in prison inspired Kalima’s motto, which he used to share with the young inmates: “Never let anyone break our minds, they may have broken our bones, broken our dreams but our minds have remained intact. I will never succumb to hatred, I will never seek revenge, I will always plead for justice and equity, I will never subject any human being to torture or illegal detention. Through the experience in prison, God’s hands have kept me. I place my destiny on his shoulders.”

[1] Capita General : Head of the prison